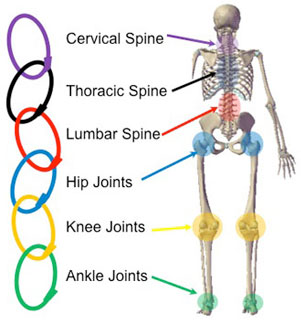

Condition the Kinetic Chain, Not the Segment, to Restore Function

Want more power, agility or speed--in any sport? The key is to train the entire body and focus on conditioning the kinetic chain as a whole. Strength and conditioning specialist Stephen Gamma walks us through a sample case study and a few recommended exercises in this recent article on Stack.com.

Whether y ou're working toward improved power, agility or speed, or working with an athlete with activity restrictions, it's important to approach training on a global scale rather than as isolated segments.

ou're working toward improved power, agility or speed, or working with an athlete with activity restrictions, it's important to approach training on a global scale rather than as isolated segments.

We know movement occurs throughout the kinetic chain. However, the degree of success hinges on appropriate activation and recruitment throughout the kinetic chain. It is easy to forget the actions and events that occur far away from the involved joint and/or segment. Juan Torres, CSCS, describes the kinetic chain to his athletes as "all work performed by the body is done as a unit. Any weaknesses in the chain will lead to dysfunction, and dysfunction will lead to decreased performance and an increased potential for injury."

For example, when greater demands are placed on grip strength, increased activation occurs in the deep "core" musculature and rotator cuff in anticipation of the need for increased joint stability. This is a prime example of how grip strength can impact the Deadlift. Should your athlete lack the necessary grip strength to lift the given load during the early pull stage, reduced spinal stability will occur, and the athlete will experience difficulty maintaining a neutral lumbar spine and hip-hinge component. Conversely, adding grip training to your overhead athletes (e.g., baseball, softball and tennis players) is a great way to increase activation to the rotator cuff complex.

Another example involves performing half-kneeling chop and lift patterns. The diagonal patterns involved in the chop and lift effectively break the "core" region into quadrants. Not only is it an effective means of identifying asymmetrical patterns, it is also a great approach for encouraging enhanced core activation prior to movement initiation of the upper extremities. If we consider the fact that we use our extremities in every athletic movement (from running to cutting and jumping) and daily living for that matter, it is very important that we create a training environment that encourages proper recruitment patterns.

Everything above applies equally when you work with athletes who have restrictions. At Pro Prospects Training Center, I recently worked with a baseball athlete who sustained a grade-2 sprain to the UCL in the thumb of his glove hand. The athlete was evaluated by his physician and placed in a cast for six weeks. His was cleared to continue baseball activity (i.e., throwing) and strength and conditioning sessions as tolerated. Recognizing the negative impact immobilization has on distal segments and the strength of cross-activation, I decided to alter his program in an effort to reduce muscle atrophy and de-conditioning.

First, I needed to understand the effects immobilizing the wrist/hand had on the rest of the extremity and beyond. A 2012 study observed decreased activation patterns of the muscles surrounding the elbow and shoulder of the involved extremity during periods of immobilization in as little as 12 hours. Realizing how a prolonged immobilization of six weeks could alter responses to proprioceptive input and subsequent changes to dynamic stability of the elbow and shoulder, I instructed the athlete to perform standing, resisted shoulder flexion and extension patterns similar to PNF patterning—although we were unable to incorporate finger/wrist flexion and extension.

His inability to hold the resistance bands prompted me to create a "sling" for the athlete out of a regular-sized towel. The athlete was instructed to perform the same movements on the opposite (contralateral), uninvolved arm, while incorporating the hand and wrist actions. I also instructed the athlete to perform One-Arm Rows, One-Arm Standing Chest Presses and grip work with the uninvolved side. My thought process was based on the concept of cross-activation, where activation of a muscle group on one side of the body has an activation potential (although to a lesser extent) on the opposite side. Similarly, as resistance increases on the "good side" (thus requiring increased recruitment), so does activation on the opposite side. This was a great way to reduce the amount of atrophy and strength loss to the immobilized segment, while keeping the athlete motivated and focused on training.

Here are some quick examples of exercises that require greater activation. Check out the link for video demonstrations of each exercise.

1. Side Plank with Row

Requires stability and resists lateral flexion. Adding the rowing component (with grip) enhances core activation with the addition of anti-rotational forces.

2. Single-Leg Bridge with Hip Abduction

The single-leg aspect places greater stress on the involved glute. Emphasizing "toes up" and pushing through the heels further encourages the "glute before hamstring" recruitment order. Controlling the moving leg away from the centerline without allowing the hip to fall creates the environment for glute involvement with anti-rotational forces.

3. Standing Cable Pull in a Single-Leg Stance

Great overall movement for, again, encouraging central recruitment prior to lower extremity movement. I find this exercise very helpful for athletes who can complete a Standing and Long Sit Toe Touch, yet have problems with a Supine Active Straight-Leg Raise or even show compensation during a dynamic warm-up (e.g., bending forward to grab the knee during a Walking Knee Hug).

For all the exercises listed above I suggest refraining from prescribing a specific number of sets and repetitions in the same fashion as a strengthening program. Instead, let the athlete dictate progression through better movement acquisition, control and decreased difficulty.

In the end, the athletes you work with depend largely on your scope of practice and facility setting. However, we can agree with confidence that whether training for performance, rehabilitation or corrective exercise, the overall emphasis should be on training the entire body and understanding how movement at one end has direct connection to an area at the other end. Understanding the importance of conditioning the kinetic chain will positively impact your program design and enhance the functional development of your athletes.

Reference:

Bolzoni F, Bruttini C, Esposti R, Cavallari P. "Hand Immobilization affects arm and shoulder postural control." Experimental Brain Research 2012;(1):63-70.

.webp)